-

- Find Care

-

- Visitor Information

- Find a Location

- Shuttles

- Visitor Policies

-

-

-

- Our Virtual Care Options

- Virtual Urgent Care

- Virtual Visits for Primary & Specialty Care

- Online Second Opinions

- Participate in Research

-

- Contact us

-

- For Innovators

- Commercialization Guide for Innovators

-

-

- Research News

- Alzheimer's Disease

- Artificial Intelligence

-

- Overview

-

- Overview

- Getting Started

- New to Mass General Brigham

- International Patient Services

- What Is Patient Gateway?

- Planning Your Visit

- Find a Doctor (opens link in new tab)

- Appointments

- Patient Resources

- Health & Wellness

- Flu, COVID-19, & RSV

- Billing & Insurance

- Financial Assistance

- Medicare and MassHealth ACOs

- Participate in Research

- Educational Resources

- Visitor Information

- Find a Location

- Shuttles

- Visitor Policies

- Find Care

-

- Overview

- Our Virtual Care Options

- Virtual Urgent Care

- Virtual Visits for Primary & Specialty Care

- Online Second Opinions

-

- Overview

- Participate in Research

-

- Overview

- About Innovation

- About

- Team

- News

- For Industry

- Venture Capital and Investments

- World Medical Innovation Forum (opens link in new tab)

- Featured Licensing Opportunities

- For Innovators

- Commercialization Guide for Innovators

- Contact us

-

- Overview

- Information for Researchers

- Compliance Office

- Research Cores

- Clinical Trials

- Advisory Services

- Featured Research

- Two Centuries of Breakthroughs

- Advances in Motion (opens link in new tab)

- Brigham on a Mission (opens link in new tab)

- Gene and Cell Therapy Institute

- Research News

- Alzheimer's Disease

- Artificial Intelligence

-

- Overview

-

- Overview

- Residency & fellowship programs

- Brigham and Women's Hospital

- Massachusetts General Hospital

- Mass Eye and Ear

- Newton-Wellesley Hospital

- Salem Hospital

- Integrated Mass General Brigham Programs

- Centers of Expertise

- Global & Community Health

- Health Policy & Management

- Healthcare Quality & Patient Safey

- Medical Education

- For trainees

- Prospective trainees

- Incoming trainees

- Current trainees

- Continuing Professional Development

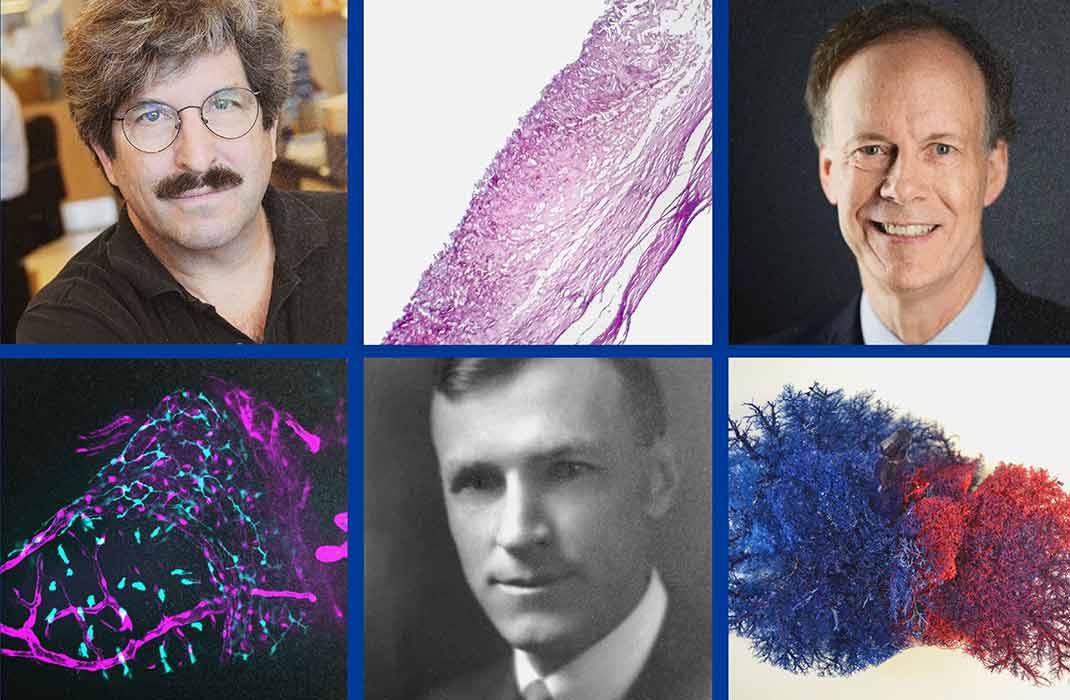

Honoring Mass General Brigham's Remarkable Nobel Legacy

The Nobel Prize is widely regarded as the pinnacle of achievement for researchers, symbolizing an extraordinary breakthrough in their field. When the Swedish chemist, inventor, and entrepreneur Alfred Nobel died in 1896, his will stated that his fortune would be used to reward “those who, during the preceding year, shall have conferred the greatest benefit to humankind.” His reward recognizes exceptional contributions to fields such as physics, chemistry, physiology or medicine, literature and peace.

Gary Ruvkun, PhD, an investigator in Molecular Biology at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) and professor of Genetics at Harvard Medical School, is the latest in a long line of researchers from Mass General Brigham to receive the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine.

Below you can learn more about Ruvkun and past winners of the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine from Mass General Brigham.

(Editor’s Note: Much of the information on the scientific accomplishments of past Nobel Winners in this article, as well as biographical details, was obtained and/or adapted from the Nobel Prize website.)

2024

Gary Ruvkun, PhD, Massachusetts General Hospital

2019

William G. Kaelin Jr., MD, Brigham and Women’s Hospital

The 2019 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine was awarded to William G. Kaelin, MD, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital (BWH) and the Dana Farber Cancer Institute. Kaelin shared his prize with Peter J. Ratcliffe, MD, and Gregg L. Semenza, MD, PhD, for their discovery of how cells sense and adapt to oxygen availability.

Animal cells need oxygen to convert food into energy through a process called aerobic respiration. While it has been known that oxygen is essential for this process, Kaelin and colleagues were the first to discover a molecular mechanism that regulates gene activity in response to changes in oxygen levels.

This discovery has far-reaching implications for treating conditions such as anemia, cancer and other diseases linked to oxygen deprivation.

Kaelin was born in New York City and pursued his interest in chemistry and mathematics at Duke University, where he also earned his medical degree. Following this, he completed his residency at Johns Hopkins University. Kaelin later served as a physician at the Brigham and a professor at Harvard Medical School, where he continued his groundbreaking work in cellular biology, ultimately earning the Nobel Prize.

2009

Jack Szostak, PhD, Massachusetts General Hospital

1990

Joseph E. Murray, MD, Brigham and Women’s Hospital

The 1990 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine was awarded jointly to Joseph E. Murray, MD, of BWH, and E. Donnall Thomas, MD, for their discoveries in organ and cell transplantation as treatments for human disease.

For a long time, organ transplantation was considered impossible due to the immune system’s rejection of foreign tissue.

In 1954, Murray's groundbreaking research overcame the barrier of organ rejection by successfully transplanting a kidney between identical twins. He prevented rejection using radiotherapy and immunosuppressants, a breakthrough that paved the way for the development of modern organ transplantation.

Murray shares this prize with Thomas for Thomas’ research on bone marrow transplantation.

Murray (1919–2012) completed his undergraduate studies at the College of the Holy Cross and later studied medicine at Harvard Medical School before serving in the U.S. Army Medical Corps during World War II. While working at Valley Forge General Hospital, he became fascinated by skin grafts, which inspired his future work in organ transplantation. After his military service, Murray joined the Peter Bent Brigham Hospital, later Brigham and Women’s Hospital, where he conducted his research in solid organ transplantation.

1953

Fritz A. Lipmann, MD, PhD, Massachusetts General Hospital

1934

George R. Minot, MD, Massachusetts General Hospital & Brigham and Women’s Hospital

William P. Murphy, MD, Brigham and Women’s Hospital

The 1934 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine was awarded jointly to George R. Minot, MD, of MGH and the Brigham, William P. Murphy, MD, of the Brigham, and shared with George H. Whipple, MD, for their discovery that a diet high in liver could cure pernicious anemia, a previously fatal disorder.

Anemia occurs when the number of red blood cells in the blood is too low. In 1926, Whipple demonstrated that a diet rich in liver could stimulate blood cell production in dogs.

Building on this discovery, Minot and Murphy applied the same principle to humans with pernicious anemia. They found that when patients consumed large amounts of liver daily, their condition improved. This breakthrough not only provided a treatment for pernicious anemia, turning an often-fatal disease into a treatable one, but also led to the identification of its cause: a deficiency of vitamin B12, a substance abundant in the liver.

Minot (1885–1950) was born in Boston, Massachusetts. He pursued his undergraduate and medical studies at Harvard University, completing his training at MGH. In 1915, he started as an Assistant in Medicine at Harvard University and MGH, later rising to senior positions. In 1922, he became the Physician-in-Chief at the Collis P. Huntington Memorial Hospital and joined the staff at Peter Bent Brigham Hospital, later the Brigham. During World War I, he served as a surgeon in the US Army. Over his career, Minot published extensively on blood disorders such as leukemia, polycythemia, and blood coagulation. He received numerous awards and honors and was an active member of various medical organizations.

Murphy (1892–1987) was born in Stoughton, Wisconsin. He earned his undergraduate degree from the University of Oregon and received his medical degree from Harvard Medical School, where he was granted the William Stanislaus Murphy Fellowship. He later joined the Peter Bent Brigham Hospital, now the Brigham, where he collaborated with Minot. Murphy continued to work at the Brigham and also taught at Harvard University until his retirement.