-

- Find Care

-

- Visitor Information

- Find a Location

- Shuttles

- Visitor Policies

-

-

- Our Virtual Care Options

- Virtual Urgent Care

- Virtual Visits for Primary & Specialty Care

- Online Second Opinions

- Participate in Research

-

- Contact us

-

- For Innovators

- Commercialization Guide for Innovators

-

-

- Research News

- Alzheimer's Disease

- Artificial Intelligence

-

- Overview

-

- Overview

- Getting Started

- New to Mass General Brigham

- International Patient Services

- What Is Patient Gateway?

- Planning Your Visit

- Find a Doctor (opens link in new tab)

- Appointments

- Patient Resources

- Health & Wellness

- Flu, COVID-19, & RSV

- Billing & Insurance

- Financial Assistance

- Medicare and MassHealth ACOs

- Participate in Research

- Educational Resources

- Visitor Information

- Find a Location

- Shuttles

- Visitor Policies

- Find Care

-

- Overview

- Our Virtual Care Options

- Virtual Urgent Care

- Virtual Visits for Primary & Specialty Care

- Online Second Opinions

-

- Overview

- Participate in Research

-

- Overview

- About Innovation

- About

- Team

- News

- For Industry

- Venture Capital and Investments

- World Medical Innovation Forum (opens link in new tab)

- Featured Licensing Opportunities

- For Innovators

- Commercialization Guide for Innovators

- Contact us

-

- Overview

- Information for Researchers

- Compliance Office

- Research Cores

- Clinical Trials

- Advisory Services

- Featured Research

- Two Centuries of Breakthroughs

- Advances in Motion (opens link in new tab)

- Brigham on a Mission (opens link in new tab)

- Gene and Cell Therapy Institute

- Research News

- Alzheimer's Disease

- Artificial Intelligence

-

- Overview

-

- Overview

- Residency & fellowship programs

- Brigham and Women's Hospital

- Massachusetts General Hospital

- Mass Eye and Ear

- Newton-Wellesley Hospital

- Salem Hospital

- Integrated Mass General Brigham Programs

- Centers of Expertise

- Global & Community Health

- Health Policy & Management

- Healthcare Quality & Patient Safey

- Medical Education

- For trainees

- Prospective trainees

- Incoming trainees

- Current trainees

- Continuing Professional Development

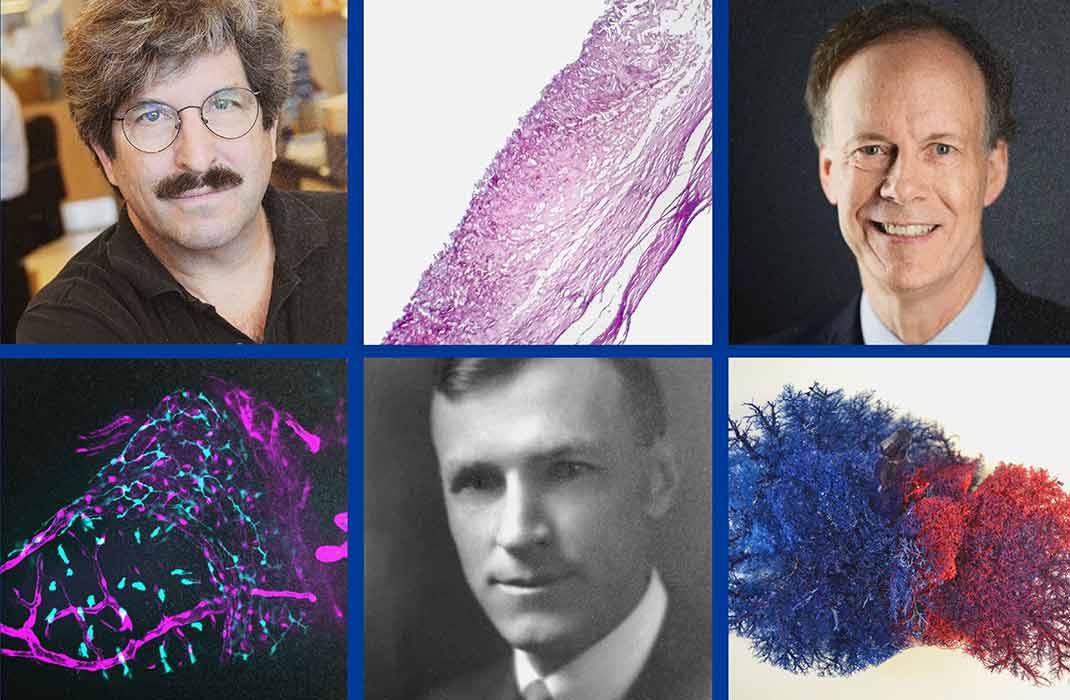

5 Things to Know About Gary Ruvkun, PhD, 2024 Recipient of the Nobel Prize for Physiology and Medicine

While we’re not (yet) experts on the complex genetic research of Gary Ruvkun, PhD, we have learned a lot about the 2024 winner of the Nobel Prize in Medicine and Physiology since the award was announced in October.

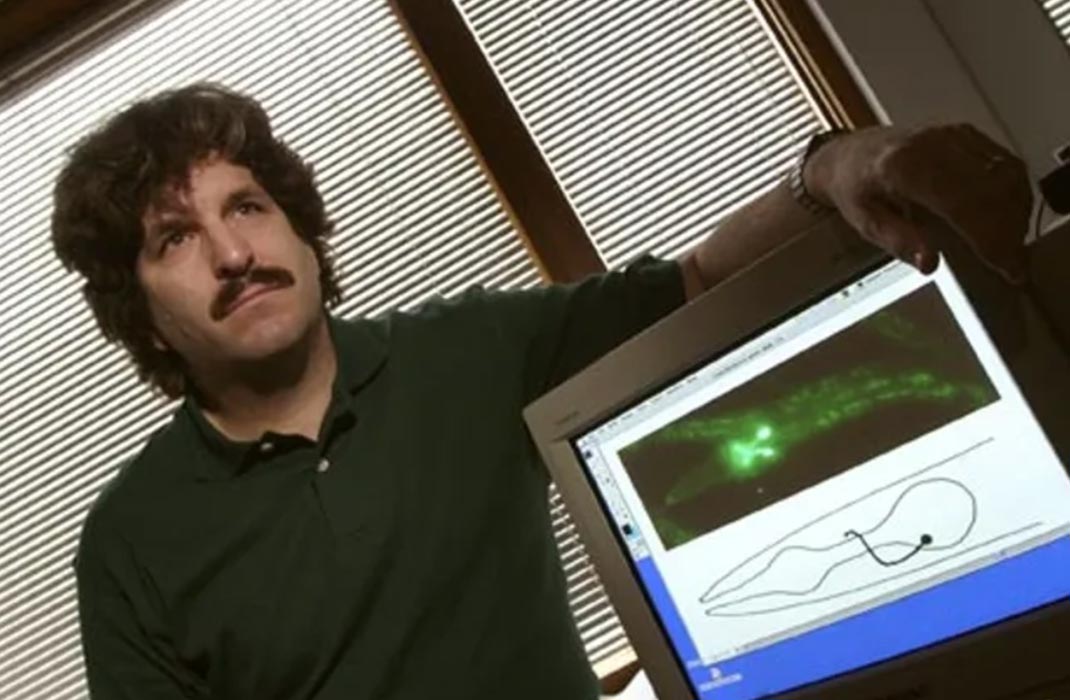

Ruvkun, an investigator in the Department of Molecular Biology at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) and a professor of Genetics at Harvard Medical School, received the Nobel along with Victor Ambros, PhD, of the UMass Chan Medical School, for their role in identifying microRNAs and defining their role in gene regulation.

Gary Ruvkun receiving his Nobel Prize from H.M. King Carl XVI Gustaf of Sweden at Konserthuset Stockholm on 10 December 2024. © Nobel Prize Outreach. Photo: Nanaka Adachi

Gary Ruvkun receiving his Nobel Prize from H.M. King Carl XVI Gustaf of Sweden at Konserthuset Stockholm on 10 December 2024. © Nobel Prize Outreach. Photo: Nanaka Adachi

Here are five things to know about Dr. Ruvkun and his unique research journey.

- Reading Scientific American in Bolivia sparked his interest to attend graduate school

After graduating from college in the early 1970s, Ruvkun was not sure what was next. Traveling had always been a passion, so he took time off to travel through the Pacific Northwest and then to Latin America.

Little did he know this journey would lead him to attend graduate school at Harvard and the start of a distinguished scientific career.

“From age 21 to 24, my career was not a direct arrow to science,” Ruvkun said. “After college, I lived in my van and planted trees in the Pacific Northwest for almost a year. Then the following year I traveled in second-class buses, in hammocks hanging on the deck of a sort of riverboat bus down 1,000 miles of the Amazon river, and on more buses all the way to Tierra del Fuego, and then onto the Andes,” Ruvkun said.

“But then after six months of travel, when I was in Cochabamba, Bolivia, I was bored for a day with travel. So, I spent a day reading Scientific American, then a monthly magazine read by the general public but written by major scientists (it is no longer like this today), and it was really a good day. And I said to myself, ‘You know what? Maybe I'll go to graduate school.’’’

- Traveling through Latin America taught him many lessons — and gave him some great stories to tell

- It took time to understand the significance of microRNA

- A microscopic worm played a huge role in making it all happen

- Research is a team effort