-

- Find Care

-

- Visitor Information

- Find a Location

- Shuttles

- Visitor Policies

-

-

- Our Virtual Care Options

- Virtual Urgent Care

- Virtual Visits for Primary & Specialty Care

- Online Second Opinions

- Participate in Research

-

- Contact us

-

- For Innovators

- Commercialization Guide for Innovators

-

-

- Research News

- Alzheimer's Disease

- Artificial Intelligence

-

- Overview

-

- Overview

- Getting Started

- New to Mass General Brigham

- International Patient Care

- What Is Patient Gateway?

- Planning Your Visit

- Find a Doctor (opens link in new tab)

- Appointments

- Patient Resources

- Health & Wellness

- Flu, COVID-19, & RSV

- Billing & Insurance

- Financial Assistance

- Medicare and MassHealth ACOs

- Participate in Research

- Educational Resources

- Visitor Information

- Find a Location

- Shuttles

- Visitor Policies

- Find Care

-

- Overview

- Our Virtual Care Options

- Virtual Urgent Care

- Virtual Visits for Primary & Specialty Care

- Online Second Opinions

-

- Overview

- Participate in Research

-

- Overview

- About Innovation

- About

- Team

- News

- For Industry

- Venture Capital and Investments

- World Medical Innovation Forum (opens link in new tab)

- Featured Licensing Opportunities

- For Innovators

- Commercialization Guide for Innovators

- Contact us

-

- Overview

- Information for Researchers

- Compliance Office

- Research Cores

- Clinical Trials

- Advisory Services

- Featured Research

- Two Centuries of Breakthroughs

- Advances in Motion (opens link in new tab)

- Brigham on a Mission (opens link in new tab)

- Gene and Cell Therapy Institute

- Research News

- Alzheimer's Disease

- Artificial Intelligence

-

- Overview

-

- Overview

- Residency & fellowship programs

- Brigham and Women's Hospital

- Massachusetts General Hospital

- Mass Eye and Ear

- Newton-Wellesley Hospital

- Salem Hospital

- Integrated Mass General Brigham Programs

- Centers of Expertise

- Global & Community Health

- Health Policy & Management

- Healthcare Quality & Patient Safey

- Medical Education

- For trainees

- Prospective trainees

- Incoming trainees

- Current trainees

- Continuing Professional Development

What Is a Defibrillator?

Chances are, you’ve seen a movie or a TV show where a defibrillator is being used on a person in cardiac arrest. The doctor puts paddles on the person’s chest, yells “Clear!” and then gives a big shock to the patient.

“Defibrillators are devices that deliver a high energy shock to the heart to stop a potentially fatal heart arrhythmia,” explains Nathaniel Steiger, MD, a Mass General Brigham electrophysiologist. Dr. Steiger treats patients with arrhythmias, or irregular heart rhythms, at Brigham and Women’s Hospital.

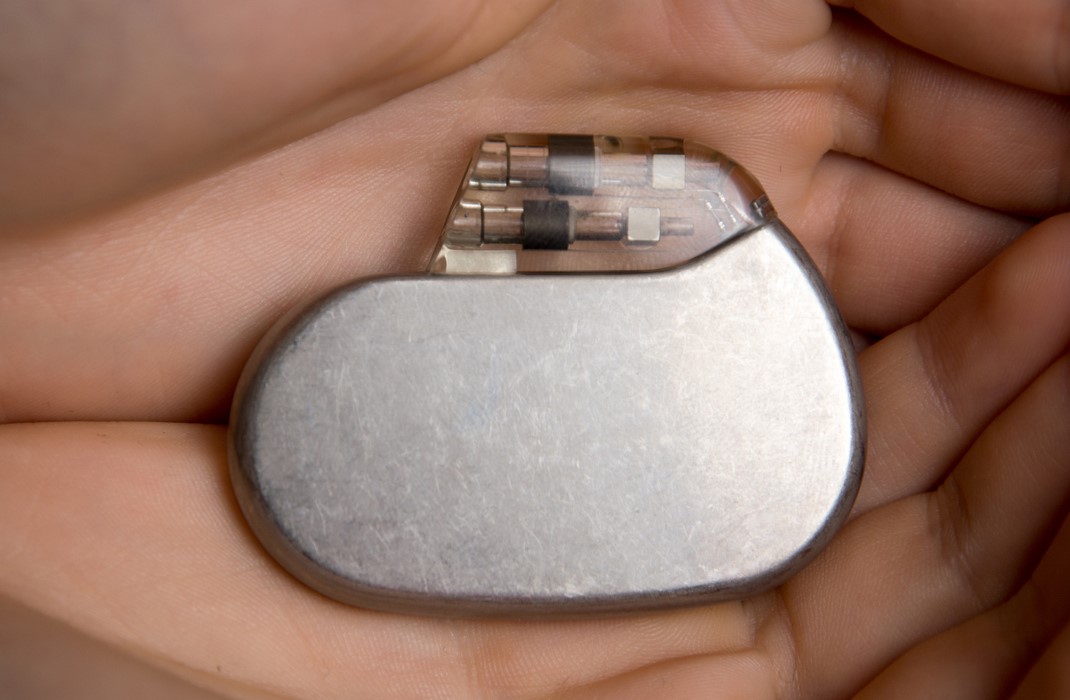

For patients who are at risk, an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) can stop the dangerous arrhythmias that cause cardiac arrest. “It’s the same concept as the paddles, just in a miniaturized form,” says Dr. Steiger.

How does a defibrillator work?

Doctors use ICDs to treat ventricular tachycardia (VT) and ventricular fibrillation (VF). Both of these arrhythmias can be fatal. ICDs are small, battery-powered devices that doctors implant in the chest near the heart. Similar to a pacemaker, ICDs constantly monitor a person’s heartbeat. Doctors position a wire, or lead, inside or near the heart, and implant the device in the left chest, under the collarbone. If the ICD detects a dangerous heart rhythm, the ICD gives a high-power electric shock to restore the heart’s rhythm.

There are two main types of ICDs—one is a transvenous ICD, and the other is a subcutaneous ICD. They are slightly different in their functionality, and each have their own advantages. A doctor may recommend a particular type of ICD based on the individual patient.

Types of ICDs

There are 2 types of ICDs, both of which have a battery longevity of 8 to 13 years:

1. Transvenous ICDs. Doctors implant these by making a small incision under the collarbone in the left chest. They access a vein through the incision and insert a wire, or lead, into the vein and advance it into the heart. Doctors fix the wire to the heart muscle with special screw. They attach the other end of the wire to the defibrillator generator, which they implant under the skin through the initial incision. Transvenous ICDs may have one, two or three wires in total, depending on the patient.

“All transvenous ICDs have pacemaker functionality, so they can pace the heart, too. Sometimes we can terminate the arrhythmia with pacing instead of delivering a shock,” says Dr. Steiger.

2. Subcutaneous ICDs. Doctors implant these under the skin; they don’t have leads that directly touch the heart.

“We prefer to use this device in some patients, because there’s less risk of lead malfunction or device infection over time,” Dr. Steiger says. However, the subcutaneous ICD can’t pace the heart, which may be important for some patients. The device is also larger than the transvenous ICD because it needs more electricity to generate the shock, so the procedure often involves general anesthesia. Future subcutaneous ICD will have additional pacing features, but they are currently not approved for use in the US.

Cardiologists may also try catheter ablation procedures, where they treat the arrhythmia circuit directly, and reduce the risk of a VT event or ICD shock. Doctors insert a thin tube into the heart to destroy the faulty cells that are the source of the arrhythmia.

ICD surgery

“We consider implanting a transvenous ICD to be a minimally invasive procedure. Usually patients come in the morning, and they go home later that day,” Dr. Steiger says. Patients are given a local anesthetic and put under conscious sedation, where they’re partially awake without feeling discomfort or pain.

During the procedure, the doctors make a small incision in the upper chest next to the shoulder. They find a vein and advance the ICD wires through the vein into the heart using x-ray guidance.

“We attach the wires to the heart muscle by deploying a little screw at the tip of the wire. Next, we attach the other end of the wire to the device, which we implant under the skin,” explains Dr. Steiger.

Subcutaneous ICDs are implanted completely under the skin and avoid placing hardware in the blood vessels or the heart. These procedures are usually performed under general anesthesia.

ICD follow-up

As part of the follow-up care post-surgery, patients see their doctor’s team within a couple of weeks, then once a year afterwards. ICDs also send reports directly to the doctor every 3 months, detailing the health of the device. If the ICD finds any arrhythmias, it notifies the doctor sooner.

“If we see an arrhythmia that’s concerning, we may order more tests to see if there’s anything new going on. We may start a new or change an existing medication. We may try a procedure to take care of the arrhythmia. Sometimes it requires reprogramming or recalibrating the device,” Dr. Steiger says.

How long does an ICD last?

Device batteries last between 6 and 13 years, sometimes longer. “It depends on person to person, and how much you use it,” explains Dr. Steiger. When it’s time for a new battery, doctors will install a completely new device.

“We make a small incision where the old device is, we take out the old device and replace it with a new one, and attach it to the existing wires,” Dr. Steiger says.

Defibrillator risks and benefits

Like pacemakers, the implantation of a defibrillator is a low-risk procedure with a risk of infection, bleeding, and damage to the heart or lungs. “The majority of people will never have to worry about these complications. They can rarely be serious,” says Dr. Steiger.

Sometimes patients can receive a shock when one isn’t indicated, called an inappropriate shock. “Rarely, the devices can get fooled. The devices have special algorithms to decrease the chances of an inappropriate shock.”

Patients can also live relatively normal lives with a defibrillator, including going through airport security or receiving an MRI, an imaging exam that uses magnetic fields. People should be cautious of the following:

High arc welding: A type of construction technique using electric fields that can interfere with the defibrillator’s function.

Standing close strong magnets, such as an induction stove: Try to stay an arm’s length away.

Cell phone: Avoid placing a cellphone within 6 inches of the defibrillator.

Cancer radiation treatment: The defibrillator should be out of the field of any radiation.

MRI scans: Most patients with new devices, and many with older devices, can safely undergo an MRI scan in a monitored setting.

Some patients receive shocks without realizing it, especially if they’re sleeping. The ICD sends reports directly to the doctors so that they can follow up with patients if there’s been an event. For patients that are aware of the shocks they receive from their defibrillators, the sensation can be intense.

“It won’t knock you off your feet, but it can definitely hurt. And it’s a problem because patients can develop PTSD or anxiety. It can really impact quality of life,” explains Dr. Steiger. The Brigham has an ICD support group, where patients can connect with other patients as well as experts on managing anxiety around ICD shocks.

Ultimately, defibrillators are an important lifesaving tool for patients with VF or VT. “Defibrillators don't necessarily make you feel better. They'll just potentially save your life. They are like a safety net,” says Dr. Steiger.

Contributor

Related articles

-

published on

-

published on

-

published on

-

published on

-

published on

-

published on

-

published on

-

published on

-

published on