-

- Find Care

-

- Visitor Information

- Find a Location

- Shuttles

- Visitor Policies

-

-

- Our Virtual Care Options

- Virtual Urgent Care

- Virtual Visits for Primary & Specialty Care

- Online Second Opinions

- Participate in Research

-

- Contact us

-

- For Innovators

- Commercialization Guide for Innovators

-

-

- Research News

- Alzheimer's Disease

- Artificial Intelligence

-

- Overview

-

- Overview

- Getting Started

- New to Mass General Brigham

- International Patient Services

- What Is Patient Gateway?

- Planning Your Visit

- Find a Doctor (opens link in new tab)

- Appointments

- Patient Resources

- Health & Wellness

- Flu, COVID-19, & RSV

- Billing & Insurance

- Financial Assistance

- Medicare and MassHealth ACOs

- Participate in Research

- Educational Resources

- Visitor Information

- Find a Location

- Shuttles

- Visitor Policies

- Find Care

-

- Overview

- Our Virtual Care Options

- Virtual Urgent Care

- Virtual Visits for Primary & Specialty Care

- Online Second Opinions

-

- Overview

- Participate in Research

-

- Overview

- About Innovation

- About

- Team

- News

- For Industry

- Venture Capital and Investments

- World Medical Innovation Forum (opens link in new tab)

- Featured Licensing Opportunities

- For Innovators

- Commercialization Guide for Innovators

- Contact us

-

- Overview

- Information for Researchers

- Compliance Office

- Research Cores

- Clinical Trials

- Advisory Services

- Featured Research

- Two Centuries of Breakthroughs

- Advances in Motion (opens link in new tab)

- Brigham on a Mission (opens link in new tab)

- Gene and Cell Therapy Institute

- Research News

- Alzheimer's Disease

- Artificial Intelligence

-

- Overview

-

- Overview

- Residency & fellowship programs

- Brigham and Women's Hospital

- Massachusetts General Hospital

- Mass Eye and Ear

- Newton-Wellesley Hospital

- Salem Hospital

- Integrated Mass General Brigham Programs

- Centers of Expertise

- Global & Community Health

- Health Policy & Management

- Healthcare Quality & Patient Safey

- Medical Education

- For trainees

- Prospective trainees

- Incoming trainees

- Current trainees

- Continuing Professional Development

What Is a Clinical Trial?

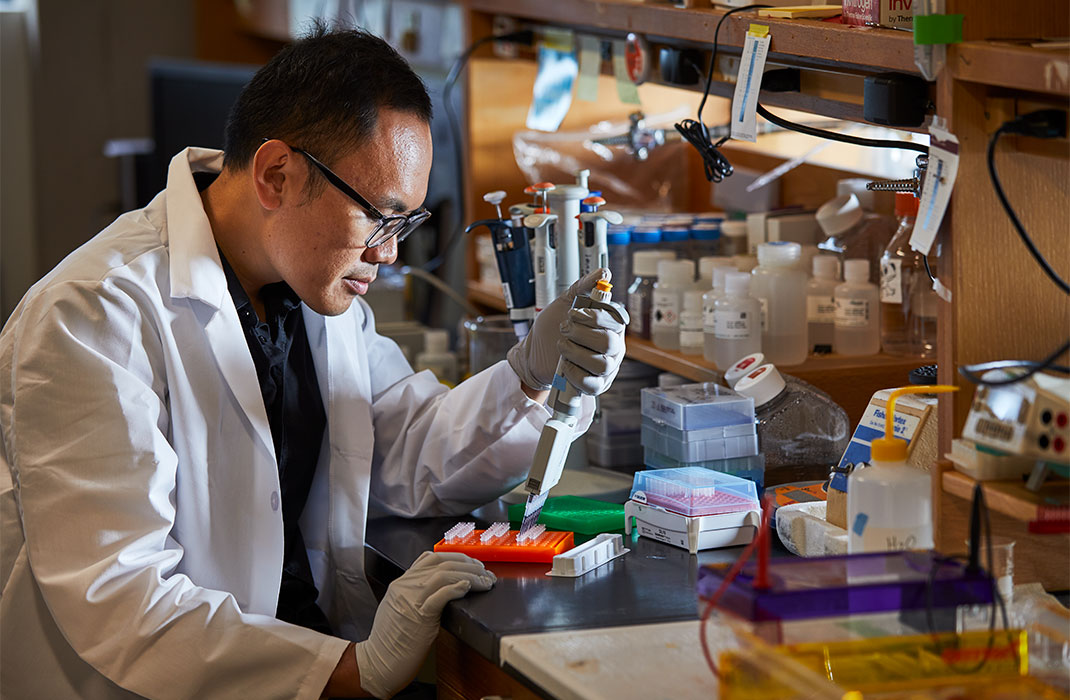

Lifesaving treatments don’t just suddenly appear inside a doctor’s office or a hospital. Years before a doctor writes a prescription, orders a test, or fits a device, a researcher asks a simple question:

“How can I improve the health of tomorrow’s patient?”

While the answer often begins in a laboratory, researchers rely on a series of tests to move solutions into the hands of doctors and patients. These tests, called clinical trials, evaluate the effects and safety of a medical intervention on humans.

Mass General Brigham is actively involved in numerous clinical trials, conducting many studies across the health system. These trials, led by our experts, hold the potential to expand the number of FDA-approved therapies in the coming years.

“Clinical trials help bridge the gap between lab bench and patient bedside,” says Bob Herman, director of clinical research at Massachusetts General Hospital. “The people who sign up for these trials are guiding medicine into a brighter future.”

He explains the different types of clinical research, the risks of clinical trials, and what questions you may consider before signing up for a trial.

What is clinical research?

Clinical research is the study of health and illness in people. It improves the way doctors treat and prevent illness.

Findings may explain how:

The body works.

Illnesses develop.

The body responds to a treatment.

Behaviors affect health.

Types of clinical studies

Researchers use two types of studies.

1. Observational studies

Researchers observe a situation. They monitor people in normal settings, collect data, and compare changes over time. Data may include the health, habits, or environments of the observed people.

Types of observational studies include:

Case study or series: A detailed description of one or more patients

Ecological study: Rates of a disease or condition compared among groups of people

Cross-sectional study: A group, or groups, studied at a specific moment in time

Case-control study: One group with a condition compared to another without the condition

Cohort study: A large group observed over time

Findings may uncover a health-related problem or trend. While researchers may propose an explanation or a solution, they put neither to the test.

A researcher may examine the diets of patients with liver cancer, for example, and notice advanced tumors only among patients with diets high in fat and sugar.

“Researchers may predict that their patients’ cancers will begin to improve if their diets do, too,” says Herman. “But, as soon as they adjust their diets, the study no longer becomes observational. The researcher has intervened, which makes the study a clinical trial.”

2. Clinical trials

Clinical trials evaluate how people respond to an intervention, whether medical, surgical, or behavioral.

Examples of interventions include:

Drugs, such as medications for high blood pressure, or hypertension

Exams, such as blood tests that diagnose diseases

Devices, such as a pacemaker

Behavior changes, such as following a diet for weight loss

Those who take part in a clinical trial do so voluntarily. Participants agree to follow the terms outlined in a trial protocol. The research team responsible for the trial writes the protocol, which explains:

Who can sign up

Test and procedure schedules

Tested drugs, devices, or diagnostic exams

Drug dosages (if applicable)

Length of study

Trial goals

Clinical trial process