-

- Find Care

-

- Visitor Information

- Find a Location

- Shuttles

- Visitor Policies

-

-

-

- Our Virtual Care Options

- Virtual Urgent Care

- Virtual Visits for Primary & Specialty Care

- Online Second Opinions

- Participate in Research

-

- Contact us

-

- For Innovators

- Commercialization Guide for Innovators

-

-

- Research News

- Alzheimer's Disease

- Artificial Intelligence

-

- Overview

-

- Overview

- Getting Started

- New to Mass General Brigham

- International Patient Services

- What Is Patient Gateway?

- Planning Your Visit

- Find a Doctor (opens link in new tab)

- Appointments

- Patient Resources

- Health & Wellness

- Flu, COVID-19, & RSV

- Billing & Insurance

- Financial Assistance

- Medicare and MassHealth ACOs

- Participate in Research

- Educational Resources

- Visitor Information

- Find a Location

- Shuttles

- Visitor Policies

- Find Care

-

- Overview

- Our Virtual Care Options

- Virtual Urgent Care

- Virtual Visits for Primary & Specialty Care

- Online Second Opinions

-

- Overview

- Participate in Research

-

- Overview

- About Innovation

- About

- Team

- News

- For Industry

- Venture Capital and Investments

- World Medical Innovation Forum (opens link in new tab)

- Featured Licensing Opportunities

- For Innovators

- Commercialization Guide for Innovators

- Contact us

-

- Overview

- Information for Researchers

- Compliance Office

- Research Cores

- Clinical Trials

- Advisory Services

- Featured Research

- Two Centuries of Breakthroughs

- Advances in Motion (opens link in new tab)

- Brigham on a Mission (opens link in new tab)

- Gene and Cell Therapy Institute

- Research News

- Alzheimer's Disease

- Artificial Intelligence

-

- Overview

-

- Overview

- Residency & fellowship programs

- Brigham and Women's Hospital

- Massachusetts General Hospital

- Mass Eye and Ear

- Newton-Wellesley Hospital

- Salem Hospital

- Integrated Mass General Brigham Programs

- Centers of Expertise

- Global & Community Health

- Health Policy & Management

- Healthcare Quality & Patient Safey

- Medical Education

- For trainees

- Prospective trainees

- Incoming trainees

- Current trainees

- Continuing Professional Development

Mindfulness App, Used to Help Youths Who Ruminate, Proves Promising

McLean Investigator Says Predictive AI Guides Who May Benefit

It was rather serendipitous. An ad for a mindfulness study posted on Instagram last year caught Avary Whitehead’s eye. He had been persistently agonizing about an unforeseen adjustment in his home life and typical stressors at school. A junior at Bishop Guertin High School, a private college-prep school in Nashua, NH, he wanted to learn more about the ad aimed at teens, hoping he might be able to calm the anxieties that had been so hard to chase.

He was 15 then, and the more he explored the initiative at McLean Hospital, recruiting 13-18-year-olds “who tend to overthink,” the more interested he became in it. As a healthcare professional, mom Kerri supported his interest, knowing how difficult the last few years have been for young people impacted by social media derisions and compounded by longstanding Covid sequestrations. Avary was accepted into the study at McLean that uses a version of the mindfulness app Headspace to quell repetitive negative thoughts (i.e., rumination). Before starting to use the app, Avary completed a battery of required pre-trial tests at the hospital, including an MRI, a computerized task, and clinical interviews.

Rumination refers to repetitive, unhelpful patterns of negative thinking, often focused on how one is feeling or a replay of stressful events, such as an interaction with a peer. Research shows that teens who are more likely to ruminate are at increased risk of depression.

The statistics are staggering. At least 15 percent of the U.S. adolescent population today experience one or more episodes of clinical depression by age 18. And there is evidence that rates of depression and self-harm among adolescents have increased over the last decade. CDC recently reported that 42 percent of high school students “felt so sad or hopeless every day for at least two consecutive weeks that they stopped doing their usual activities.” Also in the report was that 22 percent said they had seriously considered suicide in the past year.

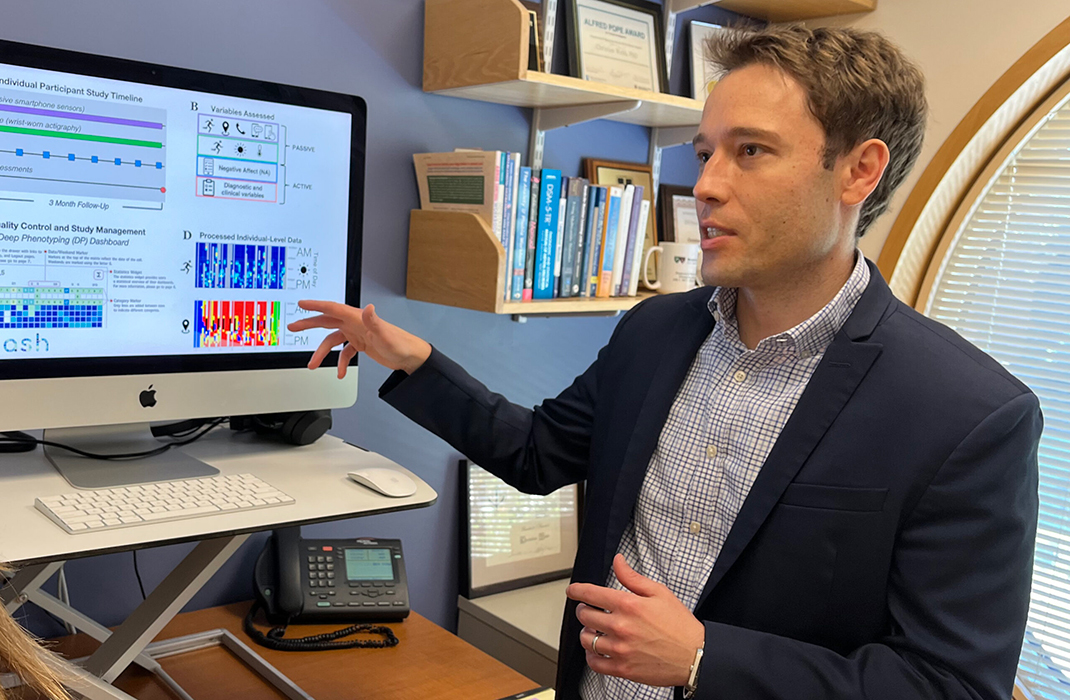

Christian Webb, PhD

Christian Webb, PhD

“Our ultimate goal,” he says, “is to develop algorithms to help identify which specific intervention is best suited for whom, so that we can move beyond the costly trial-and-error approach to treatment. This is critical because there is a growing epidemic of mental health problems with adolescents.”

Mindfulness training focuses on paying attention to the present moment, including an awareness of thoughts and feelings—in essence, a form of meditation recognized to reduce stress and anxiety. To date there are hundreds of mindfulness apps; Webb’s group has used three of them for studies in youth.

Enter the Webb Lab Headspace collaboration.

Webb and his collaborators are now testing the Headspace app in a group of 158 teens with an average age of 14, among them is Avary. The team wants to see how often the teens would use Headspace and if their rumination diminishes by using it. They also wanted to know whether results of the study would have a bearing on predicting who among them would benefit. To be enrolled, participants underwent extensive preclinical testing, comprised of symptom profiles, depression history, age, etc.

Once enrolled in the study, a research version of Headspace is downloaded on participants’ phones and the teens are encouraged to use the app daily. They are randomly assigned to a mindfulness intervention or control intervention embedded with the same Headspace app. The clinical trial is expected to conclude at the end of 2026.

Webb and his collaborators have received additional grants in the past to study mindfulness apps in youth. His current R01 NIH mindfulness grant is for $3.1 million for five years.

Anna Tierney, Clinical Research Assistant II, in Webb’s lab and head research assistant on the study, was directly involved with Avary and his mom during their participation in the study.

“It was clear from the beginning of the study,” says Tierney, “that Avary had the parental support of his mother and that they both prioritized the study and wanted to get the most out of it. That’s all that you can ask for from participants and their parents.”

Avary has praise for participating in the study, saying the app’s exercises helped him. “The app got my mind off what I was thinking. I still care a lot about school and home, but I’m not ruminating,” he said. No longer part of the study, Avary says “I am still practicing the techniques and on occasion will use the app.”

Kerri is pleased with the outcome, as well. “I noticed he was agitated with the pandemic, the family situation and school. It’s nice to see how he has learned the techniques that work. He’s taken these tools and can use them through all aspects in life.”

Friends at school know about these apps, Avary reports, not only because he has showed off his brain scan image to many of them, but also because some of his friends use mindfulness apps on their own. In fact, in health class last year, the subject was discussed by the teacher.

“We’re thankful for the app,” says Kerri. “The topic of depression is so important to me. He’s learned to normalize these tools he can use, and it’s fun to see him grow with it and bring skills to everyday life.”