-

- Find Care

-

- Visitor Information

- Find a Location

- Shuttles

- Visitor Policies

-

-

- Our Virtual Care Options

- Virtual Urgent Care

- Virtual Visits for Primary & Specialty Care

- Online Second Opinions

- Participate in Research

-

- Contact us

-

- For Innovators

- Commercialization Guide for Innovators

-

-

- Research News

- Alzheimer's Disease

- Artificial Intelligence

-

- Overview

-

- Overview

- Getting Started

- New to Mass General Brigham

- International Patient Services

- What Is Patient Gateway?

- Planning Your Visit

- Find a Doctor (opens link in new tab)

- Appointments

- Patient Resources

- Health & Wellness

- Flu, COVID-19, & RSV

- Billing & Insurance

- Financial Assistance

- Medicare and MassHealth ACOs

- Participate in Research

- Educational Resources

- Visitor Information

- Find a Location

- Shuttles

- Visitor Policies

- Find Care

-

- Overview

- Our Virtual Care Options

- Virtual Urgent Care

- Virtual Visits for Primary & Specialty Care

- Online Second Opinions

-

- Overview

- Participate in Research

-

- Overview

- About Innovation

- About

- Team

- News

- For Industry

- Venture Capital and Investments

- World Medical Innovation Forum (opens link in new tab)

- Featured Licensing Opportunities

- For Innovators

- Commercialization Guide for Innovators

- Contact us

-

- Overview

- Information for Researchers

- Compliance Office

- Research Cores

- Clinical Trials

- Advisory Services

- Featured Research

- Two Centuries of Breakthroughs

- Advances in Motion (opens link in new tab)

- Brigham on a Mission (opens link in new tab)

- Gene and Cell Therapy Institute

- Research News

- Alzheimer's Disease

- Artificial Intelligence

-

- Overview

-

- Overview

- Residency & fellowship programs

- Brigham and Women's Hospital

- Massachusetts General Hospital

- Mass Eye and Ear

- Newton-Wellesley Hospital

- Salem Hospital

- Integrated Mass General Brigham Programs

- Centers of Expertise

- Global & Community Health

- Health Policy & Management

- Healthcare Quality & Patient Safey

- Medical Education

- For trainees

- Prospective trainees

- Incoming trainees

- Current trainees

- Continuing Professional Development

Signs of an Opioid Overdose: How to Help in an Emergency

We are in the midst of our country’s worst overdose crisis. In 2021, 220 people died each day in the United States from an opioid overdose according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

“It may be hard to tell whether a person is experiencing an overdose,” says Ali Raja, MD, Mass General Brigham emergency medicine doctor and executive vice chair of the Department of Emergency Medicine at Massachusetts General Hospital. “If you aren’t sure, treat it like an overdose.”

If you suspect someone may be experiencing an overdose, here’s what you can do to potentially save a life:

Step 1: Check for signs of an opioid overdose.

Signs of overdose may include:

Small, constricted “pinpoint pupils”

Falling asleep or losing consciousness

Not responding to noise or physical stimuli

Slow, weak, or no breathing

Choking or gurgling sounds

Limp body

Cold and/or clammy skin

Discolored skin (especially in lips and nails)

Step 2: Call 9-1-1.

Call 911 if you think someone may be overdosing.

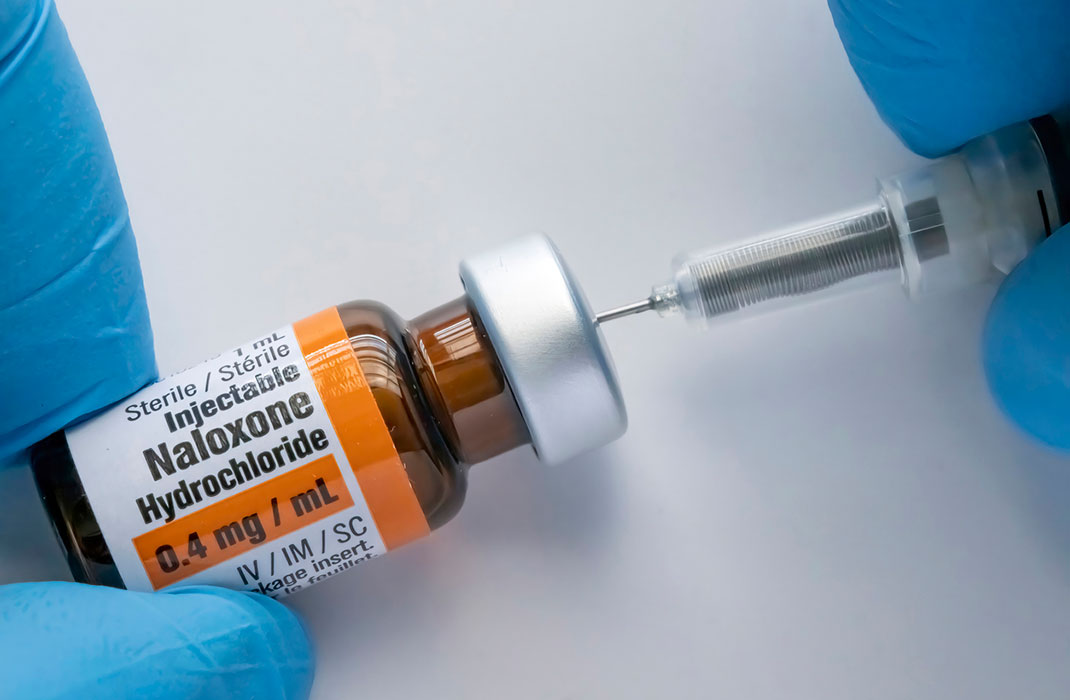

Step 3: Give the person naloxone, if available.

What is naloxone?

Step 5: Stay with the person until emergency assistance arrives.

“Coming upon someone experiencing an overdose can be scary,” Dr. Raja says. “But if you follow the right steps, you may help save a life.“

Naloxone: Be prepared to help a loved one

If someone you know is at increased risk for opioid overdose, you should carry naloxone and keep it at home. You can request naloxone if you know someone who takes opioids, or was prescribed an opioid medication. Currently all 50 states, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico allow pharmacists to dispense naloxone without a prescription and naloxone is now an over- the-counter medicine.

What increases risk of opioid overdose?

Anyone who takes opioids can overdose and should be offered naloxone. The following factors increase risk of opioid:

A history of overdose

Patients with sleep-disordered breathing

Patients taking benzodiazepines with opioids

Patients at risk of returning to a high dose for which they have lost tolerance. For example, patients undergoing tapering or recently released from prison.

Patients taking higher dosages of opioids

A history of substance use disorder

If any of the above applies to you, a family member, or someone you know, talk to a clinician, pharmacist, or local health department for options in your community.

Do I need special training to give naloxone to someone who has overdosed?

Being familiar with naloxone can help put your mind at ease in an emergency. Many local pharmacies and community-based programs offer training to use naloxone. The CDC has many resources on opioid overdose prevention that can help you support your loved one and prepare for emergencies.

Contributor