-

- Find Care

-

- Visitor Information

- Find a Location

- Shuttles

- Visitor Policies

-

-

-

- Our Virtual Care Options

- Virtual Urgent Care

- Virtual Visits for Primary & Specialty Care

- Online Second Opinions

- Participate in Research

-

- Contact us

-

- For Innovators

- Commercialization Guide for Innovators

-

-

- Research News

- Alzheimer's Disease

- Artificial Intelligence

-

- Overview

-

- Overview

- Getting Started

- New to Mass General Brigham

- International Patient Services

- What Is Patient Gateway?

- Planning Your Visit

- Find a Doctor (opens link in new tab)

- Appointments

- Patient Resources

- Health & Wellness

- Flu, COVID-19, & RSV

- Billing & Insurance

- Financial Assistance

- Medicare and MassHealth ACOs

- Participate in Research

- Educational Resources

- Visitor Information

- Find a Location

- Shuttles

- Visitor Policies

- Find Care

-

- Overview

- Our Virtual Care Options

- Virtual Urgent Care

- Virtual Visits for Primary & Specialty Care

- Online Second Opinions

-

- Overview

- Participate in Research

-

- Overview

- About Innovation

- About

- Team

- News

- For Industry

- Venture Capital and Investments

- World Medical Innovation Forum (opens link in new tab)

- Featured Licensing Opportunities

- For Innovators

- Commercialization Guide for Innovators

- Contact us

-

- Overview

- Information for Researchers

- Compliance Office

- Research Cores

- Clinical Trials

- Advisory Services

- Featured Research

- Two Centuries of Breakthroughs

- Advances in Motion (opens link in new tab)

- Brigham on a Mission (opens link in new tab)

- Gene and Cell Therapy Institute

- Research News

- Alzheimer's Disease

- Artificial Intelligence

-

- Overview

-

- Overview

- Residency & fellowship programs

- Brigham and Women's Hospital

- Massachusetts General Hospital

- Mass Eye and Ear

- Newton-Wellesley Hospital

- Salem Hospital

- Integrated Mass General Brigham Programs

- Centers of Expertise

- Global & Community Health

- Health Policy & Management

- Healthcare Quality & Patient Safey

- Medical Education

- For trainees

- Prospective trainees

- Incoming trainees

- Current trainees

- Continuing Professional Development

Caring for a Child With Down Syndrome

Down syndrome is among the most common genetic conditions in the world. More than 217,000 people in the United States have the condition, and about 5,100 babies in the U.S. alone are born with it each year.

Parents naturally may have lots of questions about the condition and wonder if their children may face future health and development challenges. Brian Skotko, MD, MPP, a Mass General for Children medical geneticist, assures parents and family members that people with Down syndrome can thrive. In fact, they lead fulfilling lives and bring joy to their friends and family.

“There has never been a better moment than now to be born with Down syndrome,” says Dr. Skotko. “While the science hasn’t changed and the genetics haven’t changed, we as a society have changed and continue to change to accept, include, and value people with Down syndrome.”

Dr. Skotko is the Emma Campbell Endowed Chair on Down Syndrome at Mass General for Children. He’s part of a multidisciplinary team that cares for patients in the Down Syndrome Program. Dr. Skotko explains what causes Down syndrome and how parents and caregivers can best prepare for, and support, a child with Down syndrome.

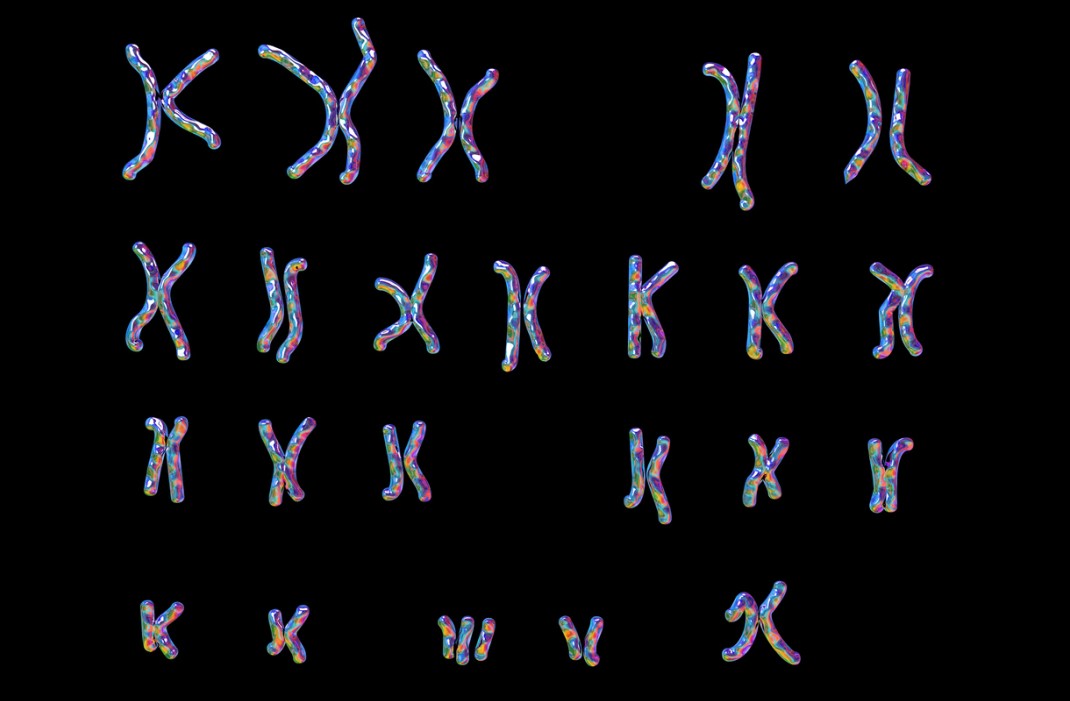

How many chromosomes do people with Down syndrome have?

- Trisomy 21: There is an extra 21st chromosome, forming a trio. The trio appears in every cell. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), about 95% of people with Down syndrome have Trisomy 21.

- Translocation Down syndrome: The extra copy of the 21st chromosome attaches itself to another chromosome, such as chromosome 13, 14, or 15. This form of Down syndrome can also be inherited. Parents can carry the genetic precursor for this type of Down syndrome and can pass it down to their child, who might then develop the condition. About 3% of people with Down syndrome have translocation. Like Trisomy 21, the extra copy appears in every cell.

- Mosaic Down syndrome: Some cells, but not all, have the extra chromosome. About 2% of people with Down syndrome have mosaic cases.

How is Down syndrome diagnosed?

Parents may choose Down syndrome screening or testing during pregnancy. Such testing is a personal decision and optional.

Babies can also be diagnosed with a blood test after birth, too.

Screening blood test

According to the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), doctors can screen for the likelihood of a child having Down syndrome during pregnancy. From the results of their screenings, a pregnant person may choose to undergo another round of tests to confirm a diagnosis.

- First and second-trimester screenings: Between weeks 10 and 13 of pregnancy, or weeks 15 and 22 of pregnancy, parents can opt for a blood test to estimate the chances of their child having Down syndrome.

- Combined first- and second-trimester screening: Combining the results of these blood tests offers a more accurate prediction.

- Cell-free DNA testing: The placenta, a connective tissue linking a parent to their developing child, releases small amounts of DNA into the bloodstream of a pregnant parent. Starting at week 10 of pregnancy, doctors can extract a sample of this DNA — called cell-free DNA — and assess its makeup.

Signs of Down syndrome during pregnancy ultrasound

Prior to testing, doctors can also screen for Down syndrome using an ultrasound. The test uses high-frequency sound waves to create images of the unborn child during the first and second trimesters of pregnancy.

Fluid behind the neck of the child can sometimes signal the condition and patients may choose to proceed with testing. An ultrasound can also assess for heart conditions.

Diagnostic tests: Amniocentesis (amnio), chorionic villus sampling (CVS), and percutaneous umbilical blood sampling (PUBS)

Screening is not perfect. Sometimes, a screening test falsely predicts a diagnosis. A diagnostic test can help confirm or clarify the results of a screening.

During diagnostic tests, a doctor analyzes a genetic sample from a person who is pregnant. They can extract cells from amniotic fluid (amniocentesis), the placenta (chorionic villus sampling), or blood from the umbilical cord (percutaneous umbilical blood sampling).

Characteristics of Down syndrome

Down syndrome was named after John Langdon Down, a British doctor first credited for describing the unique characteristics of those with the condition. While the condition generally occurs equally across different races and ethnic groups, it occurs slightly more in males than females.

Signs of Down syndrome in babies

Newborns with Down syndrome typically present physical characteristics of the condition at birth. They include:

- Low set ears

- Short fingers

- Wide gaps between first and second toes

- Indented nasal bridge

- Upward slanting eyes

The characteristics of trisomy 21 and translocation Down syndrome are identical. Those with mosaic Down syndrome may express some, but not all, of these characteristics.

“It's important to note that these are just characteristics,” says Dr. Skotko. “These in and of themselves are not medical problems, but they're some of the features that allow us to distinguish whether or not someone might be born with Down syndrome.”

Treating Down syndrome

A cure for Down syndrome does not exist. Guidelines for treating co-occurring conditions, however, do.

Common health conditions in children with Down syndrome

People with Down syndrome typically experience several other health conditions. The most common include:

Down Syndrome Clinic

Down Syndrome Clinic to You (DSC2U) helps caregivers and primary care physicians anticipate and learn about health conditions in people with Down syndrome of all ages. DSC2U is a virtual platform where caretakers can respond to a series of targeted questions and receive automated answers and customized recommendations. The clinic provides checklists, which allow caregivers to share recommendations with their loved one’s primary care provider (PCP).

Dr. Skotko recommends people with Down syndrome work closely with their doctors to ensure they stay up to date on recommendations.

“We’re aiming to democratize health care so everyone with Down syndrome can access the best, most up-to-date care that exists,” says Dr. Skotko. “We’re coming to you, so you don’t have to come to us.”

What is the current life expectancy of someone with Down syndrome in the United States?

The average lifespan of someone with Down syndrome is close to 60. Thanks to advances in medicine and technology, Dr. Skotko thinks the best has yet to come for individuals with the condition.

“I would expect life expectancy to continue to expand,” says Dr. Skotko. “Research is continuing to uncover new answers to the mysteries that we still have for people with Down syndrome.”

Research breakthroughs in Down syndrome

One promising breakthrough is a surgically implanted device often referred to as a “pacemaker for the tongue.” The device has been shown to drastically improve the sleep apnea symptoms of adolescents and adults with Down syndrome.

The Down Syndrome Research Program at Massachusetts General Hospital collaborates with researchers worldwide to better understand the condition. The center offers families opportunities to participate in an array of studies, many of which have explored:

Improvement of language, memory, and attention among adults

Drugs for depression

Quality-of-life measurements

Nutrition and weight management